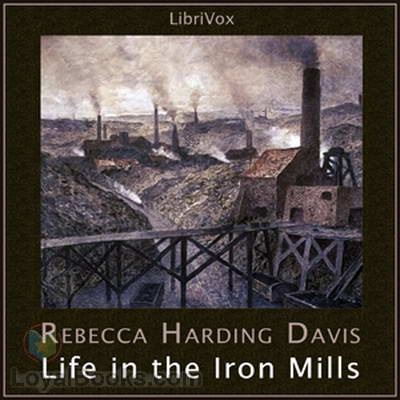

Out of all the authors that we have read so far, Melville’s Tartarus of Maids is the most similar to Davis’ Life in the Iron-Mills. Both of them are very alike in that they portray the real and horrific working conditions that they witnessed during their lives. Yet like the book says, even the Tartarus of Maids “falls short of the grim picture of living and working conditions [Davis] paints” (1824). However, even with the many similarities between their works, Davis’ work struck me as being much different than Melville’s because of her happy ending.

Yes, Davis paints a very bleak and

depressing picture of life in the iron-mills, but she also attempts to show

that there is more than that: that there is still hope for change. Her ending, while it isn’t exactly “happily

ever after,” presents an optimistic view of the future. Even the statue, with its “mad,

half-despairing” look (1834), is presented as being a symbol of hope:

"While the room is yet steeped in heavy shadow, a cool, gray light suddenly touches [the statue's] head like a blessing hand, and its groping arm points through the broken cloud to the far East, where, in the flickering, nebulous crimson, God has set the promise of the Dawn" (1849).

While Davis ends her story looking towards the future and the possibility of a better life, Melville only ends with a lamentation, exclaiming “Oh! Paradise of Bachelors! and oh! Tartarus of Maids!” (Melville). Melville’s story presents the idea that the horrors of industrialization are due to greed. The end of the Tartarus of Maids implies that the narrator will continue to use that particular paper mill because it is cheaper, and thus the seeming hopelessness of the situation is left unsolved and nothing changes.

Both Davis and Melville show the horrors

of the working conditions of the time, but while Davis remained optimistic

about the future, Melville obviously did not seem to think that the conditions

were going to improve any time soon.

They are both excellent writers, but being the fairy-tale fan that I am,

I much prefer Davis’ work.

Works Cited

Melville, Herman. The

Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids. Electronic Text Center, University of

Virginia Library. Retrieved from

Blackboard, ICC. 7 December 2012.

Perkins, George, and Barbara

Perkins. The American Tradition in Literature. 12th ed. Vol. 1. Boston.

McGraw-Hill, 2009. Print.

Frederick Douglass

is still well renowned for his writings on his experiences in slavery, and he is

by far the best writer - in terms of technique - of the slave authors we have read

so far.

Frederick Douglass

is still well renowned for his writings on his experiences in slavery, and he is

by far the best writer - in terms of technique - of the slave authors we have read

so far.